Homework for November 14th

Answer one or more of the following questions about the first short story in A Contract With God (titled the same thing):

1. What role does religion and ethnicity play in the story A Contract With God?

2. How does Frimme react to his daughter's death? If God really did violate their contract, is Frimme justified in his actions afterward?

3. What is the significance of the young boy finding the old contract at the end of the story, and what is the significance of how he finds it?

4. What is the role of class struggle and the American Dream in the story?

Response by Zachary Fagan

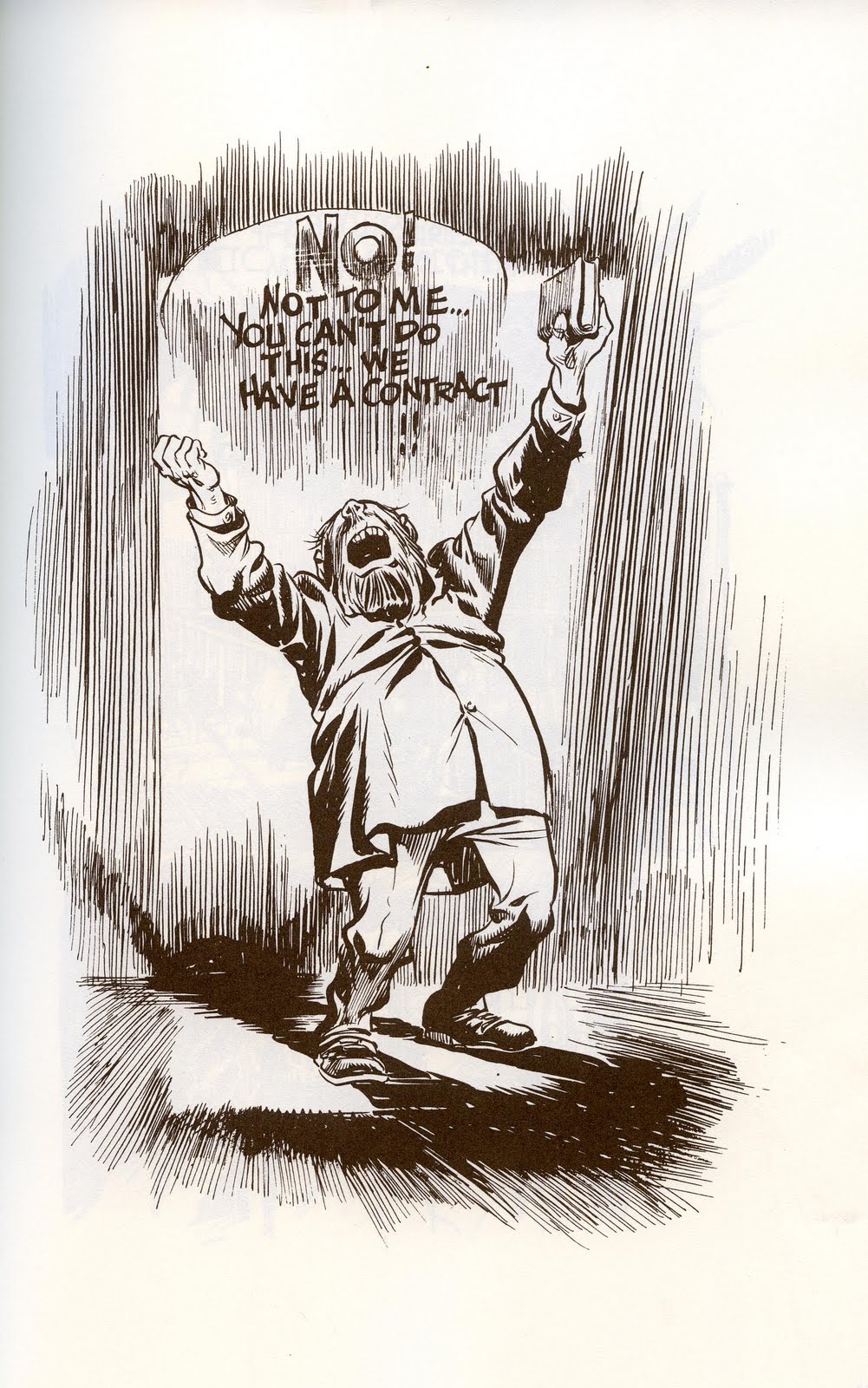

ResponderExcluirIn response to question three, Frimme has an understandably angry reaction to his daughter's untimely death, However, it is his actions afterward that seem to turn him from an admirable man into a detestable character.

The story "A Contract With God" is full of religion, primarily focuses on the theme of faith. In it, it is almost as if the “contract” that Frimme makes with God is more of a one way agreement, as God never agrees to this contract. However, in his mind, Frimme thinks he deserves to experience life without misfortune because of it, saying ‘If God requires that men honor their agreements...then is not God, also, so obligated?” (25). This seems to highlight a major flaw in religion as a whole and its followers. Fremme believed that he could pick and choose what he wanted to follow, being good not to just be good, but because he thought he was getting a reward for it. His actions after the death of his daughter, in turn, did not surprise me. Once he realized that being good and following the “contract” was not getting him what he wanted, he gave up and turned toward a negative way of living. The shaving of his beard not only has religious implications, but personal ones as well. By cutting of his hair and changing his appearance, it indicates that the old Frimme was dead, the “good” Frimme - “For the first time, he committed an act which formerly was unthinkable” (34).

Overall, this “contract” was never really a contract, as it God did not agree to and therefore unable to violate it. Though the death of his daughter caused emotional distress, it is important to see the motivations behind Frimme’s actions both before and after her death.

After his daughter's death, Frimme took the money from the synagogue's funds, he had helped maintain, to buy himself the building he had lived in since he arrived in America. Once he owned the building he immediately raised the rent by 10% and continued to make changes the decreased the quality of living for the building's tenants. He also took a "shikseh." In his eyes, God broke their contract by killing his daughter so he was justified in acting badly as God was no longer giving him rewards for acting well.

ResponderExcluirHowever, the situation is not as simple as that. After the Holocaust many Jewish people found themselves questioning why the "all-loving God" would have punished them in such a way. The answer that many came up with was that God didn't punish them but rather let it happen for a greater purpose. With this theory in mind, God may not have killed Frimme's daughter, thereby not breaking the contract, but may have let her die as part of a greater plan for Frimme- which he was disqualified from participating in by reacting the way he did. There is also the nuance that technically God had been rewarding Frimme for many years previous as he had been saved from death like the rest of his village and he had thrived once coming to America. Technically God had given him many rewards. If God did break the contract by killing his daughter it may have been because Frimme had not done enough on his part of the contract- perhaps God wanted him to do more than just being well-behaved and to do something great for others. Similarly, it seems that he made up for it by giving Frimme such success with his real estate business, "his success appeared to be as much the result of uncanny luck as anything else."

There are many arguments for why Frimme was not justified in doing what he did because God did not break the contract, however, there is one overarching reason for why he has: there is no worse pain, no worse punishment than the feeling of a parent after their child dies. Whether God was personally involved in his daughter's death or not, the all powerful figure that Jews believe he is could have prevented it. I think because of that God did break their contract and Frimme was justified in his actions. He lost his daughter despite an entire life of while not being extraordinary, being good. While he may not have fulfilled all aspects of the contract, he did not deserve the retribution that he received.

Kevin Hautigan

ResponderExcluirThe young boy finding the contract at the end of the story is impactful because it represents the intergenerational continuity of religion. Frimme Hersh felt his contract with God was violated when his daughter died, but he later returned to religion to fill emptiness in his life, as many people do. Then, after making a new contract with God and finding new purpose in life, he died. The young boy who finds the tablet with the contract finds it after “...he saved three kids…” (p. 57). The boy’s story seems to be a carbon copy of Frimme’s as he finds the contract after being recognized for the good he has done. This demonstrates that religion often attracts many of the same type of people: those that do good and embrace love. Will Eisner is likely trying to show the reader that religion and belief in God can destroy the lives of those with such strong hearts, as it did to Frimme. He also proves that this is not a rare occurrence as it is something that occurs generation after generation.

Additionally, the young boy finds the contract while, “...being trapped in the alley of number 55 by three toughs” (p. 58). This symbolizes religious persecution, similar to persecution that Frimme once faced, as the boys pick on him for being different. Eisner also has the boy find the contract while hurling rocks at his attackers in order to demonstrate that religion, or a sort of covenant with God, can serve as a beacon of hope in the face persecution. Eisner truly wants to convey the comfort religion can provide those in need, particularly good-hearted youth, before it fails you and your faith is ripped from you in times of tragedy.

3. I reacted very strongly to the ending when the young boy finds the old contract because to me, it just seemed as though the viscous cycle was repeating and that it may never end. Thinking about it more now, however, I can see it interpreted as a fresh start for the young boy, indicating that the outcome of his life will be better than Frimme’s. Yet because the situations are so similar, I’m much more inclined to believe this is not the case.

ResponderExcluirFrimme was born the year Tsar Alexander II died, which resulted in horrific Jewish pogroms. The young boy is bullied. Frimme was altruistic to others, and so is the young boy. Both are Jewish. Both make a contract with God and at a young age.

2. Frimme reacts to his daughter’s death by making his own contract. He uses the Temple’s bonds to purchase a tenement, and he continues to build his housing empire. He eventually pays back the Jewish elders with interest but dies before he can put his new contract with God into place.

The second part of the question is more philosophical. If it is true that God is morally perfect, then he could not have violated the contract. If he did violate the contract, then he is not morally perfect. This is under the assumption that keeping one’s word is morally preferred. It seems though, however, that there is no evidence that Frimme ever made real contact with God, if such a being was or is even there, and so we have no way of knowing if such a contract was ever agreed upon to begin with.

Mike Neary

~Sorry, I meant to post THIS one~

ExcluirMike Neary

3. I reacted very strongly to the ending when the young boy finds the old contract because to me, it just seemed as though the viscous cycle was repeating and that it may never end. Thinking about it more now, however, I can see it interpreted as a fresh start for the young boy, indicating that the outcome of his life will be better than Frimme’s. Yet because the situations are so similar, I’m much more inclined to believe this is not the case.

Frimme was born the year Tsar Alexander II died, which resulted in horrific Jewish pogroms. The young boy is bullied.

Frimme was altruistic to others, and so is the young boy.

Both are Jewish. Both make a contract with God and at a young age.

In effect, the young boy has seemingly come across a curse that likely will be passed on to yet another unsuspecting human being. This caused me to feel a sense of being trapped when I read it, and it caused me both frustration and remorse that Frimme’s outcome is likely now to be translated into the young boy’s future. The lives of both are, literally and figuratively speaking, set in stone from the start.

2. Frimme reacts to his daughter’s death by making his own contract. He uses the Temple’s bonds to purchase a tenement, and he continues to build his housing empire. He eventually pays back the Jewish elders with interest but dies before he can put his new contract with God into place.

The second part of the question is more philosophical. If it is true that God is morally perfect, then he could not have violated the contract. If he did violate the contract, then he is not morally perfect. This is under the assumption that keeping one’s word is morally preferred. It seems though, however, that there is no evidence that Frimme ever made real contact with God, if such a being was or is even there, and so we have no way of knowing if such a contract was ever agreed upon to begin with.

But if God had violated the contract, then I believe the justification Frimme’s reaction is mixed from the standpoint of utilitarianism. While Frimme ultimately repaid the Temple’s elders back the money with interest and bequeathed them the tenement, he also raised the interest rates on the residents (50), evidently putting a strain on them but also greatly aiding the future of the Temple’s followers. If taken on a basic numbers calculation, there were likely more residents negatively affected than people in the Temple. Yet if taken more on a value basis, the magnitude of the negative effects spread out over a larger number of residents experienced was likely individually not as harmful as the individual benefit the Temple experienced obtaining both interest and a lease to an entire tenement.

Andres Gonzalez

ResponderExcluirIn response to question 2, Frimme essentially abandons his faith and allows for human temptations and greed to drive his actions. At first, Frimme was depicted as an honorable and respected man that was loved in his community. Frimme did many good deeds in his community, and “faithfully and piously, he adhered to the terms of his contract with God”. However, he is driven to question his faith by the death of this daughter. Much like in The Book of Job, both the characters question their faith because of the suffering in their lives, and each story tackles the question “If God requires that men honor their agreements… then is not God also so obligated?” (25).

In these two stories, it is shown that God does not need to oblige to men because He is simply higher being. Job realizes this, but Frimme fails to do so and continues to believe that he and God can have a contractual agreement. He is obsessed with creating a “genuine contract with God” (50), although this is not possible. However, although a contract with God is technically impossible because God does not have to honor His side of the bargain, this does not mean that Frimme’s actions were justified. Frimme had a lot to be grateful for in the story, and this had to do with him being a good person by following his faith. However, just because one terrible thing happened to him, this does not mean that he has the right to behave in the manner that he did. His mistake was believing that the "contract" was the thing that gave him good fortune in life. He was happy because he was a good man, but when life finally hit him he blamed it on the supposed contract. He began to act selfishly and even jeopardized other people in the process by becoming a greedy man that was driven mad due to his selfish actions that never made him happy. He was not justified in doing this because this “contract” was never possible and never had an impact on his life. Therefore, he had no real reason to act in such a selfish manner, and only did so to spite the “contract” he had with God.

After the pious Frimme Hersh’s daughter unexpectedly passes away, he responds by giving up his faith and focusing instead on material possessions. He is devastated when he receives the news and responds by renouncing his contract with God. To Hersh, his daughter’s death represents a clear violation of the contract he had established with God, and he proceeds to shave his beard, stop saying the Morning Prayer, and marry a non-Jewish woman. Additionally, he lies and uses the synagogue’s money without permission to purchase the tenement on 55 Dropsie Avenue and subsequently worsens the living conditions of his former neighbors to turn a profit; “Raise the rents 10% Mr. Cragg!!” “But what about Missus Kelly? She’s on a widow’s pension from Ireland!?” “No exceptions!” (Eisner, 51) Based on the information the reader is presented, Frimme’s response to his daughter’s death is completely justified. Prior to giving up his faith, Frimme devoted his entire life to helping others despite the intense hardship he’d endured from a young age with his parents passing away and then growing up in a low-income neighborhood in New York City. Hersh then comes to the conclusion that there exists no way to enforce his contract with God because God cannot be held accountable for his sins the way man can be. “ If God requires that men honor their agreements… …Then is not God, also, so obligated??” (Eisner, 41) Thus free of his moral obligation to be a good person, Hersh becomes a greedy, self-serving tycoon until his mistress reminds him of his former faith. Although I believe Hersh’s reaction to his daughter’s passing was reasonable, Eisner makes sure to illustrate that there are many other people who are put into this same situation and choose to respond differently. The passing of one’s daughter was not unusual in this community and Hersh justified the renouncing of his faith because he had a contract with God. However, as demonstrated by the conversation between the synagogue elders, all religion is a contract between man and God, and Hersh’s contract was not “ a deviation but an abbreviation.” Thus Hersh held himself to a different standard to everyone else, and only in context of that standard are his actions justified.

ResponderExcluir-Shrenik